Baltimore's sewage system is in trouble. Sanitary sewage outfalls allow untreated sewage to spill into our streams during rainstorms. Overflowing pipes spill water into our streets, and even our basements. And major capital improvements are needed at our wastewater treatment facilities and throughout the system for Baltimore to clean up our waterways that lead to the Inner Harbor and keep pollution out of our neighborhoods.

A consent decree signed last year by Baltimore City, the Maryland Department of the Environment, and the EPA outlines the steps that Baltimore must take to fix these problems over the next 13 years. Last week, the Department of Public Works hosted the first annual public information session about its progress on those steps – one of the transparency and accountability mandates in the agreement.

One of the biggest sources of sewage contamination in our streams is the prevalence of Sanitary Sewage Overflow (SSO) sites: outlets that let raw sewage run directly into the Gwynns Falls, Jones Falls, and other local streams. When our sewage system was built a century ago, these were a key design feature to prevent sewage overflowing into people's homes by providing an alternative outlet. But through increasing the system’s capacity and repairing pipes so rainwater can’t leak in, these overflow sites can be eliminated – and must be eliminated to achieve healthy streams and a clean Harbor. DPW reported that, in addition to the two known remaining SSO locations (at 836 E Preston St and on Falls Road near the streetcar museum), fifteen more were discovered in the past year, making it more difficult to close them all. Overflows happen from each outlet routinely, and the consent decree requires these overflows to be reported to the public; you can see overflows from each location by month here.

Closing SSOs requires making sure the system has enough capacity not to be overwhelmed, and completing just one project will reduce overflows by 80%: the $430-million Headworks project at the Back River Wastewater Treatment Plant, where a misaligned 12’-diameter pipe leading to the city has caused miles of backed up sewage for years. DPW reported at the meeting that this project is on track to be completed by 2020; read more about it here.

This year, DPW is developing a set of plans required by the consent decree for preventing sewage overflows, addressing spills and basement back-ups, and improving maintenance on the whole system to prevent leaks and sinkholes. We'll keep you up to date as they do - and let you know when these plans don't look like enough to keep everyone's neighborhoods sewage-free.

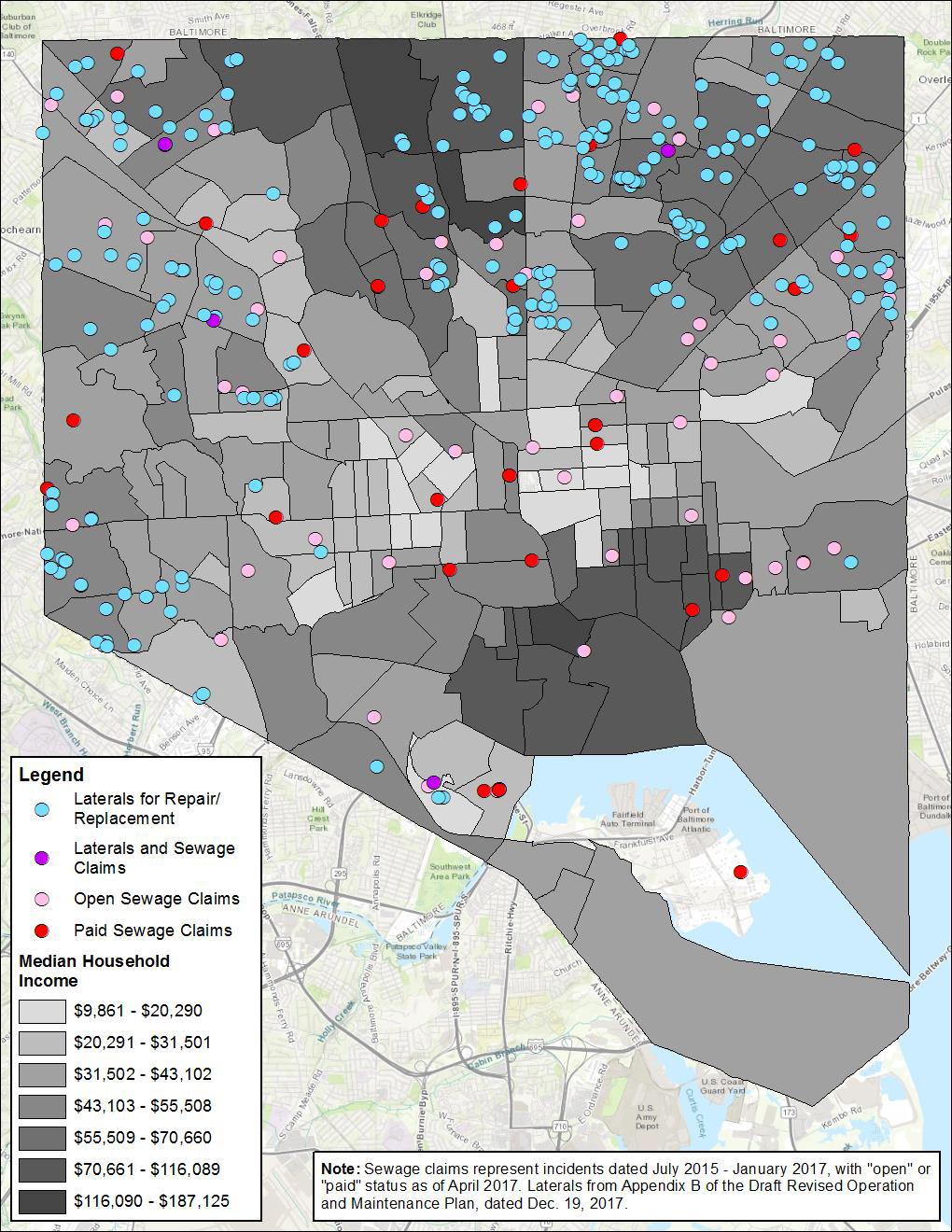

The Operations and Management Plan has already been published (PDF), and it includes one piece of the City's plan to address building back-ups of sewage: its program for finding, prioritizing, and repairing broken or leaking lateral sewage lines (the pipes carrying sewage from homes to the sewer main lines under the streets) that cause building back-ups. According to an analysis by the Environmental Integrity Project, the process the City plans to use to find laterals that cause building back-ups may fail to find laterals that contribute to back-ups in low-income neighborhoods. 48% of claims for damage from basement back-ups submitted to the City Law Department from July 2015 through February 2017 were for buildings in census tracts with an average household income of less than $42,000. However, only 27% of laterals causing back-ups identified through City's program are in those neighborhoods. (The map above illustrates this pattern: although the pink and red dots indicate that sewage back-ups in buildings occur throughout the city, laterals marked for replacement and repair by blue dots are clustered to the north and west.) We're working with the Environmental Integrity Project to make sure the city doesn't overlook sewage problems in low-income communities and prioritizes those needs in future plans. You can read more details and recommendations in our comments to DPW here:

In February, the city will publish its Emergency Response Plan for dealing with overflows of sewage inside people's homes. Have you experienced a basement back-up? Did you report it to the city? How, and what happened afterward? If you have a story to share, please get in touch with me. Hearing from you before the plan is published will help us find better ways to keep Baltimore's basements sewage-free.