As a burgeoning anthropologist, I have had to come to terms many times over with the history of the discipline. The use of words like “primitive” or “exotic” used to describe what we see as the “other”— A way in which to remove ourselves from the reality of our shared humanity. In all honesty, it has always been a point of contention in my full embrace of the discipline, simply because, there is much less difference between us and the “other” than we’d like to believe.

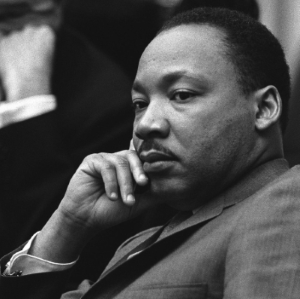

In some of my research, I called on the philosophies of our great American activists like Mamie Till Mobley, Nina Simone, James Baldwin, and of course, the great Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. To connect the study of people, culture, and what makes us human with the work of great humanitarians seemed like obvious synergy. To curate and produce authoritative knowledge on people requires a deep level of knowing that Dr. King was committed to throughout his life. He didn’t simply preach about what he heard – he spoke about what he observed and lived through—right next to his fellow man.

In anthropological research, the work of ethnography is crucial to creating understanding of a people. Ethnography requires deep physical immersion into the culture and context of those we hope to learn more about, thereby creating a rich and full narrative. Now, when this work is done in a community with which the researcher identifies, it is called a native ethnography. Committed to the study of oneself and one’s own people, Dr. King was the epitome of a native ethnographer.

An example of his ethnographic skill and commitment that resonates with me was one of his trips to Chicago. Dr. King visited Homan Ave, a street in a predominately Black neighborhood, in the dead of winter in 1966. Upon arrival, he came to learn that many of the tenements in which people and their families resided, were without heat. Temperatures were below zero and many people’s lives wagered on their ability to access heat. Dr. King was offered the opportunity to reside in a hotel across the city, and he declined. He chose to stay with the people in this neighborhood and advocate for them from their position. He helped those he was living with from his own funds and access to labor by cleaning up the buildings and paying for repairs to restore heat. He then spent additional time lobbying city officials to immediately address the beyond subpar living conditions. Even though Dr. King was sometimes admonished by his own advisors for his level of commitment (and risk), it was this ethnographic immersion that educated him deeply on the plight of those he was working to aid. He won victory for his extended community as the city followed his visit with special interest in the neighborhood that led to city sponsored pest extermination and the advent of building inspectors verifying adherence to codes.

Another integral component to ethnographic research is the production of a rich narrative, curated through “thick description.” This kind of description and storytelling comes from the physical placement into a community or culture, repeated observations of human interactions, and inquisition of the meaning of said interactions. By deepening the level of one’s understanding to this point, the ethnographer is able to create a narrative by which to explain the operations and perceptions of a community clearly. Dr. King took this work a step further and utilized narrative to fuel his activism. In Letter from a Birmingham Jail, we see how Dr. King used his compilation of this ethnographic observations to create a rich narrative for the advocacy of those dismissed, discriminated against, and disenfranchised. This quote from the letter echoes that meaning:

“We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed. For years now, I have heard the word 'wait.' It rings in the ear of every Negro with a piercing familiarity. This 'wait' has almost always meant 'never.' The nations of Asia and Africa are moving with jetlike speed toward the goal of political independence, and we still creep at horse-and-buggy pace toward the gaining of a cup of coffee at a lunch counter. I guess it is easy for those who have never felt the stinging darts of segregation to say "wait." But when you have seen vicious mobs lynch your mothers and fathers at will and drown your sisters and brothers at whim; when you have seen hate-filled policemen curse, kick, brutalize, and even kill your black brothers and sisters with impunity. Then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait. There comes a time when the cup of endurance runs over and men are no longer willing to be plunged into an abyss of injustice where they experience the bleakness of corroding despair.”

This quote, among others, highlights Dr. King’s lived understanding that “wait and see” almost never works. It requires bravery, conviction, and sacrifice to create meaningful change.

As we take the legacy of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. forward, I challenge us to sit deeply with the experiences of those that are aligned with us, and those that challenge our understandings of the world. Through this practice of intentional immersion, we are more equipped to make a sustaining change to the benefit of us all.