Hey everyone — Gabe here, with Recycling Electronics for Climate Action and current student at the University of Minnesota.

As a sustainability intern, I spend a lot of time thinking about climate justice and environmental health. But nothing prepared me for what I learned when I dug into a part of our campus most students never see: where our old electronics actually go.

Before my tour of the UMN ReUse Program Warehouse, I already knew that e-waste poses some problems. These are a few of the common warnings:

- Electronics contain lead, cadmium, mercury, and PFAS-like compounds that pose a health risk

- When tossed into landfills, these toxins may leach into groundwater

- Runoff eventually reaches rivers, lakes, and ecosystems, especially in Minnesota where our water table is shallow

- E-waste is one of the fastest-growing waste streams globally, and yet it’s also one of the most recyclable

Seeing what actually happens to our campus electronics — what gets reused, repaired, recycled, or thrown out — really made it hit home.

Walking Into the Warehouse: “Four Percent of the University’s Entire Waste Stream Passes Through Here”

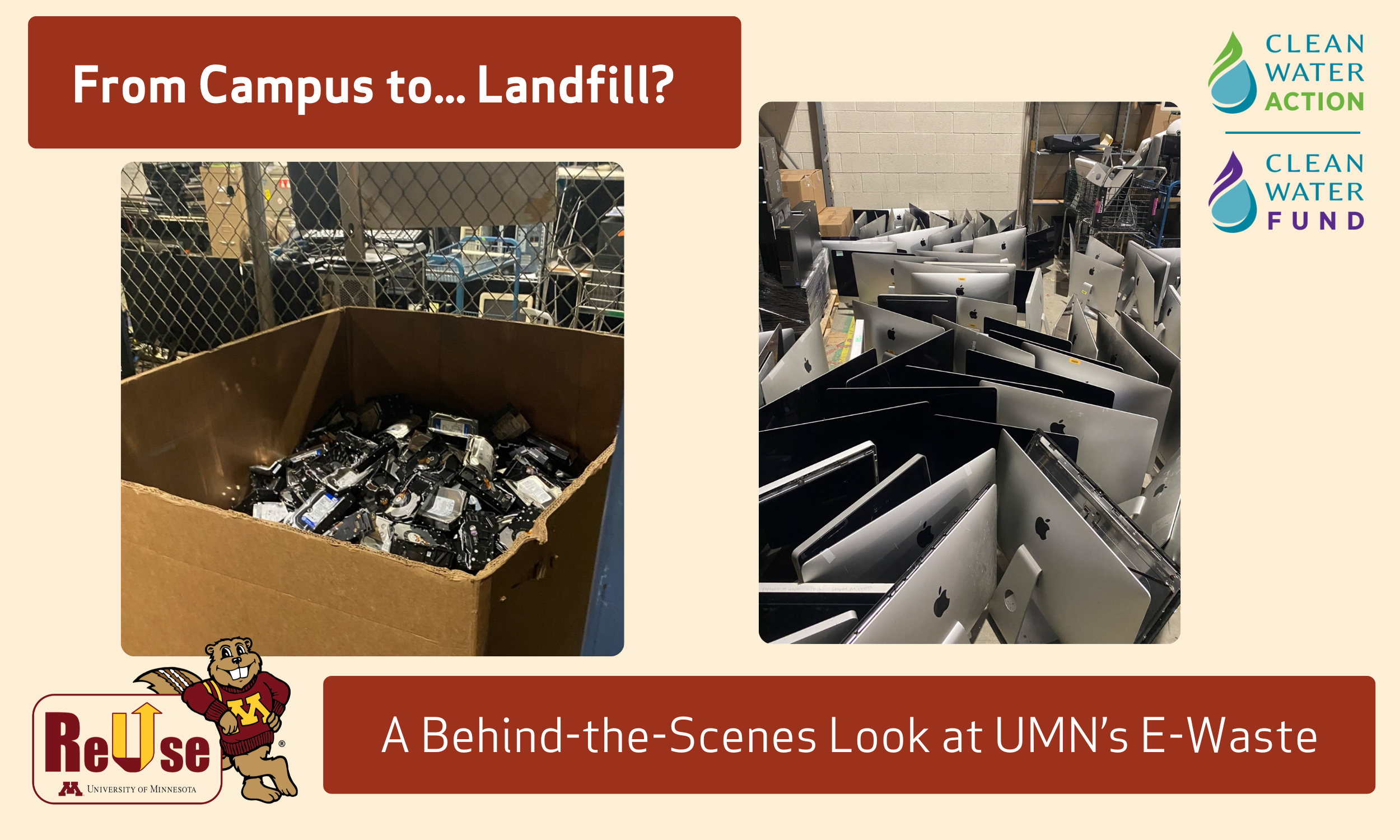

When I stepped into the ReUse warehouse for the first time, I was hit by the size of it — rows of furniture, shelves of cords, towers of computers, Apple products stacked like dominoes waiting to be processed. Only 4% of all UMN waste goes through the ReUse Program, but that 4% contains some of the most valuable and environmentally harmful items: electronics.

The ReUse staff described their role as “a secondary processor” — the last chance an item has before becoming e-waste. A staff member explained the situation perfectly:

Just because an item can be discarded or recycled doesn’t mean that’s the best environmental option. Reuse always comes first.

And they really mean it.

Everything starts at the loading dock, where bins from departments across campus are dropped off. From there, the ReUse team sorts items into two categories:

- Data-containing electronics (computers, tablets, phones, hard drives — anything with storage) go to the secure IT cage.

- Non-data electronics (keyboards, mice, cables, monitors, lab equipment, etc.) go to general processing.

But even before a device is categorized, one question must be answered: Can it be reused? This is where the environmental impact becomes clear.

Reusable vs. Recyclable: How to Decide?

I asked the team how they choose what gets reused, repaired, or recycled, and their answer surprised me—there isn’t a textbook formula. It’s a mix of different factors:

- Condition

- Age

- Reusability

- Energy efficiency (deep freezers and older fridges are so energy-hungry that it’s better to recycle them)

- Data security risk

- Demand vs. available space

Some items, like minus-80°C lab freezers, never make it to the ReUse center. Instead, these get shipped off to specialty recycling centers like Dynamic (UMN’s main e-waste recycler) and Cloud Recycling (Roseville). Higher-value items that still function well, like stainless steel refrigerators, might get auctioned. Many electronics will go through a triage process: remove parts, weigh components, price and sell what’s usable, recycle the rest.

Dealing with Data & Product Design

Inside the IT cage in the ReUse center, I watched as staff pulled apart desktops, removed hard drives, and fed them into a crusher. Crushed drives are sent to Northern Metals, which buys metals and computer components as scrap. This system ensures that toxic e-waste stays out of landfills, which ultimately protects groundwater and prevents heavy metals from entering Minnesota waterways.

But for data security reasons, if the ReUse team can’t get wipe permission through the University's Office of Information Technology or if the storage is soldered in, the device has to be sent into the recycling stream — even if it's in perfect condition.

One issue the ReUse team kept mentioning shocked me more than anything else: Apple devices are becoming nearly impossible to reuse. Modern MacBooks and iPads have soldered-on storage, meaning data can’t be removed without destroying the device.

“We’re at the mercy of product design,” they told me. “A 2019 MacBook worth hundreds of dollars ends up getting crushed because we can’t safely wipe it.”

This is exactly why product design is so important. Electronics that can’t be opened or repaired become waste — long before they need to be.

114.6 Tons of E-Waste in One Year

According to UMN’s sustainability dashboard, the University produced 114.6 tons of e-waste in the 2024 fiscal year, and older estimates reach up to 200 tons per year. But what really surprised me was hearing ReUse team said they’re bracing for an increase.

Why?

The Windows 10 end-of-life deadline.

Departments across campus are soon retiring thousands of devices simply because they can’t run Windows 11. Most are still functional and could have been reused, but the university is constrained by software requirements. This could cause a one-year tsunami in e-waste entering the warehouse and adding even more e-waste to the ReUse center's stream.

It's just another example of how one small product design decision by a major company can have such a huge impact on waste generation downstream.

Students Are Part of the Problem — and the Solution

While touring, I asked how many students even know this place exists. They laughed — a tired, knowing laugh. According to Ahnika, a ReUse staff member, “People don’t know we’re here. I talk to UMN staff who have never heard of us.” Which is wild, because the ReUse warehouse is one of the best sustainability resources on campus!

Students can buy:

- a keyboard and mouse for under a dollar,

- monitors for cheap,

- dorm furniture,

- lab equipment,

- office chairs,

- cords, cables, and chargers

—and tons more.

Every item a student buys is one less purchase from corporations like Amazon, and one less device entering the waste stream. As Ahnika told me:

We get more keyboards and mice than we can sell. If more students came, we could divert so much more.

Why This Matters for Water Quality

When electronics aren’t correctly handled, pollutants like heavy metals and flame-retardants could leach into soil and groundwater. These pollutants have a variety of different health risks:

- Lead damages brain development

- Cadmium accumulates in kidneys and fish

- Mercury enters aquatic food chains

- Brominated flame retardants contaminate lakes

- Microplastics from shredded electronics enter waterways

Minnesota’s rivers and lakes — including the Mississippi watershed that runs right through our campus — are especially vulnerable. Every device reused instead of discarded is one less toxic load that could end up in our water system.

What Students Can Do Right Now

1. Visit the ReUse Program

883 29th Ave SE in Minneapolis

Thursdays are public sale days; check their website for more information.

2. Donate or recycle your electronics responsibly

During move-out, the ReUse center has donation bins in the front entrance of every dorm.

3. Spread the word

Most students don’t know about the ReUse Warehouse. Tell your friends and classmates!

4. Support responsible e-recycling rules and laws in your region and state

Policy changes can be made at the University level, too. The UMN Board of Regents could support prioritizing repairable devices in future purchasing, and funding for additional staff hours to remove and wipe hard drives instead of buying new ones.

Walking out of the warehouse that day, I felt a mix of hope and urgency. Hope because UMN’s ReUse Program is doing incredible work with limited staff, limited time, and limited space. Urgency because the system relies on students and departments actually participating.

E-waste isn’t just a waste issue. It’s a water quality issue, a human health issue, and a climate justice issue.

And the first step to solving it is simple: Keep things in use. Take advantage of local resources like the ReUse Program. Repair instead of dumping. Buy secondhand before buying new.

Small actions matter, especially when 114 tons of e-waste per year are on the line.