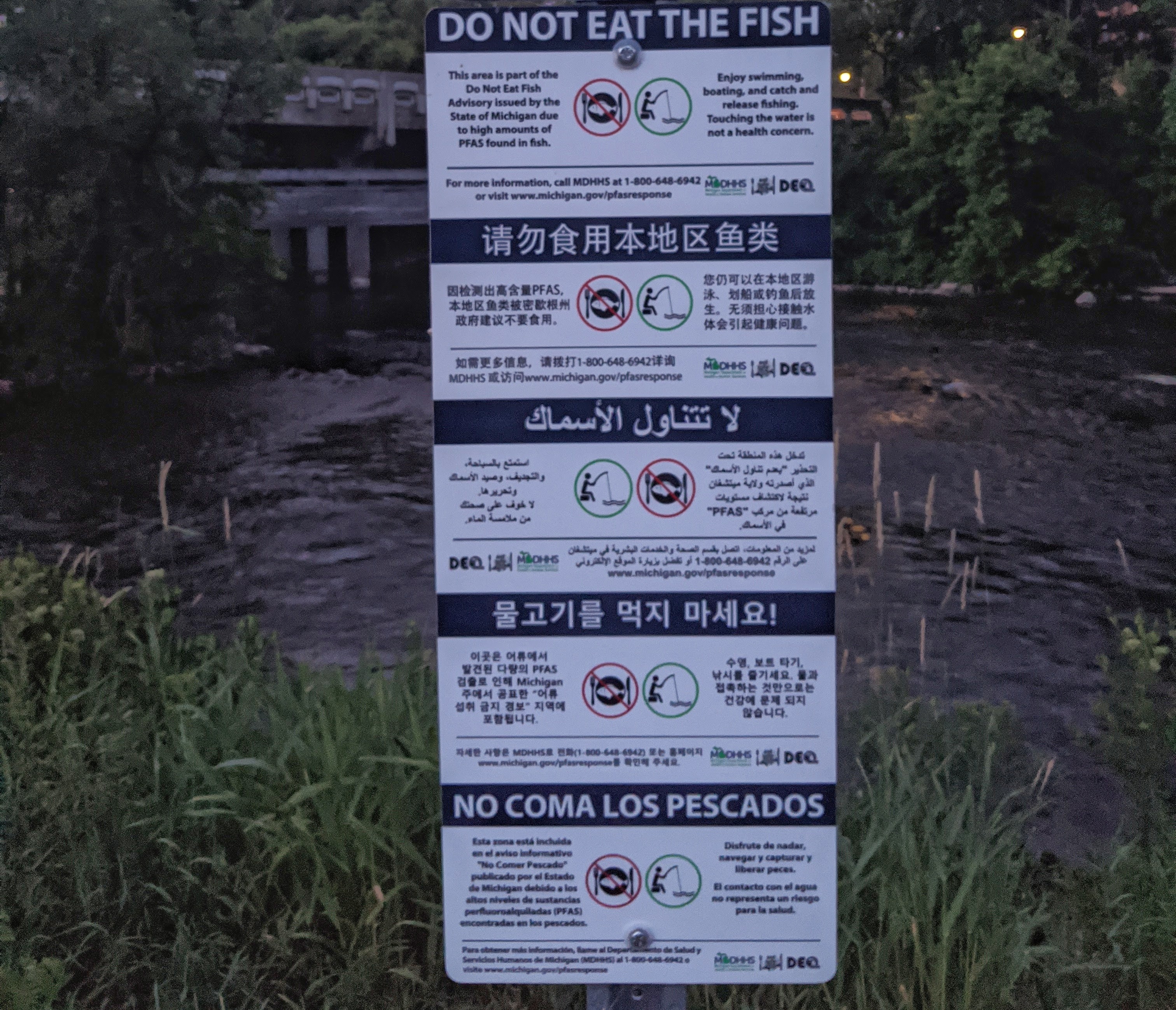

In states across the country, Clean Water Action is tackling the PFAS pollution problem. PFAS (per- and polyflyoroalkyl substances) is known as the "forever chemical" because it persists in the environment and in our bodies. It is associated with a range of health harms from cancers to liver impacts to reproductive issues. PFAS can impact communities in a variety of ways so we will be share updates from spots across the country in the coming weeks to highlight some of these local impacts. Stay tuned and let us know if you'd like to get involved locally!

On August 3rd, after over a year of workgroups, public comment, and deliberation, Michigan finalized new drinking water standards on seven PFAS chemicals that are among the strongest current standards in the country. PFAS broadly refers to a family of thousands of chemicals used in a variety of products including firefighting foam, non-stick surfaces, water repellent and stain resistant fabrics, cleaning products, chrome plating, and grease resistant food packaging. Unfortunately, PFAS chemicals are also hazardous to human health and development and high levels of PFAS in the bloodstream can cause certain types of cancer, thyroid disease, low birthweight, and a variety of other problems. PFAS chemicals can be harmful in very small amounts. Lead for example, is measured in parts per billion and while no amount of lead is safe or healthy, Michigan’s lowest in the country drinking water standard is 5 parts per billion. PFAS chemicals on the other hand are measured in parts per trillion, with the new PFAS standards ranging from 6 to 400,000 parts per trillion. To put that in perspective, one part per trillion is roughly the equivalent of one drop in 20 olympic-sized swimming pools.

Setting these standards was not easy. Clean Water Action members from across the state submitted public comments, staff worked in the Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE) stakeholder groups, and together we pushed state authorities to create strong, science-based standards for PFAS chemicals. Getting these seven standards in place was a big victory, but there is still a long way to go.

One of our concerns around these ‘forever chemicals’ is the fact that over 4,700 of them exist, and we really only have enough data to regulate about 18 of them. That means that the entire process, over a year in the making, that went forward to set standards on seven chemicals could happen again and again and again as more data becomes available until all 4,700+ chemicals are properly regulated to protect public health and our environment.

In setting the current standards, the state didn’t even fully consider impacts on the most vulnerable individuals, pregnant mothers and infants. PFAS bioaccumulates and is passed through breast milk. A strong argument could be made that the current standards are not stringent enough to protect the health of pregnant mothers and infants. As more studies are done and more people are exposed to PFAS, we will know more about long-term impacts. For the time being, knowing what we know now, it seems that the best course of action would be to follow the precautionary principle and if anything, err on the side of setting overly stringent standards.

One of the major roadblocks to setting stronger standards is the Environmental Rules Review Committee (ERRC). The ERRC is one of the “fox in the henhouse” panels established during Governor Synder’s last year in office to oversee rulemaking and permitting at EGLE. It is a panel comprised mainly of industry representatives, not toxicologists or other experts, that now has a major role in setting new environmental standards. These new PFAS standards were about as stringent as one could envision passing that panel without serious delays.

One great option for regulating a family of chemicals that we know are dangerous, but don’t have clinical studies on all 4,700+ individual chemicals to regulate each on its own, would be by taking a class-based approach to regulating PFAS. We could view the PFAS family not as 4,700+ individual chemicals, but as one family of chemicals that we know are harmful to human health and difficult if not impossible to remove from the environment. Knowing this, we could regulate all highly-flourinated compounds as one class instead of continuing to regulate them each individually.

Other common sense solutions that ought to be pursued by the state legislature include requiring all products containing PFAS chemicals to be labelled as such, eliminating the use of fluorinated firefighting foam (as Ann Arbor Fire Department already has), and passing polluter pay bills that have been introduced each term over the last few years, yet haven’t even received hearings despite massive public support. Fixing our PFAS problem will not be easy or cheap. The corporations who are responsible for contamination that currently impacts over 2 million Michigan residents should be paying for the solutions, instead of relying on taxpayers to pay for a problem caused by the negligence of successful corporations. As it stands, our new standards are a big step in the right direction, but we have a long way to go. It may not be possible to fully address our PFAS contamination problem until we address another pervasive problem – the influence of corporate money on our political process.