As we continue to explore the impacts of environmental justice and climate change, it's crucial to highlight the unique challenges faced by New Jersey's incarcerated individuals. Sydnie Bogan, a Graduate Research Assistant at Kean University, has conducted pivotal research under the guidance of her advisor, under the guidance of Assistant Professor, Dr. Galia Shokry, which delves into these pressing issues. Bogan's work sheds light on the compounded environmental and health risks experienced by those incarcerated in New Jersey, who are often left vulnerable due to their circumstances.

Understanding the Crisis

New Jersey's 13,196 incarcerated individuals confront numerous challenges, from restricted mobility and exposure to hazardous conditions to inadequate healthcare. The state, with the highest number of contaminated sites in the nation at 13,495, places a significant portion of its prison facilities directly on or near these sites. This proximity exposes incarcerated individuals to a range of harmful substances, including lead, arsenic, carcinogens, E. coli, and other hazardous bacteria in soil and groundwater.

Climate Change Exacerbates Vulnerabilities

New Jersey faces significant climate challenges, including rising temperatures, sea levels, and increased flooding and heatwaves. These climate impacts further jeopardize the health of incarcerated individuals, who are predominantly African American (59%) and Hispanic (14%), and often originate from pollution-burdened communities. The inability of incarcerated individuals to avoid hazardous environmental conditions heightens their susceptibility to conditions such as respiratory and heart diseases. Recent inspections have highlighted unsafe living conditions and sanitation problems.

- Environmental Contamination:

- Half of New Jersey's state prison facilities are located on contaminated sites, with the remaining facilities within a mile of such sites.

- Contaminants include lead, arsenic, carcinogens, E. coli, and other hazardous bacteria in soil and groundwater.

- Climate Change Vulnerability:

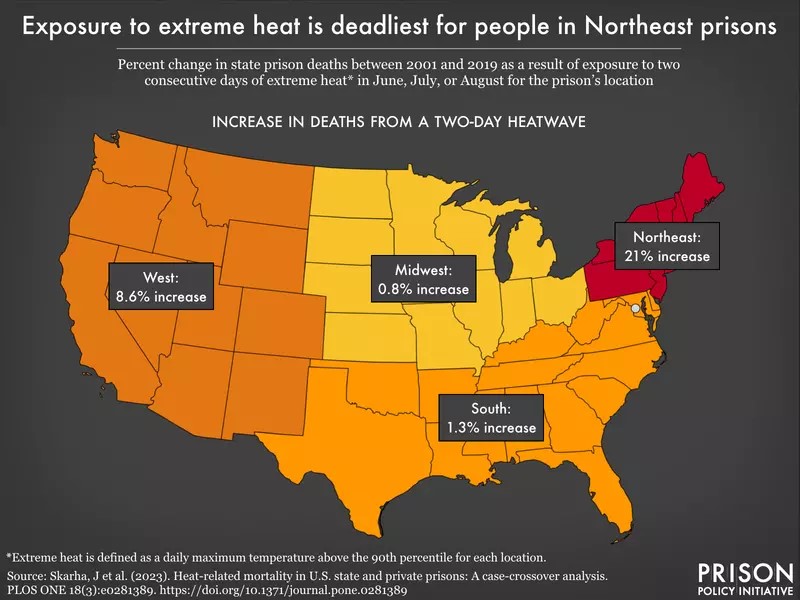

- Many prison facilities lack full temperature control, leading to cells reaching up to 94°F during summer heatwaves.

- Warmer seasons and heavy rainfall contribute to mold and mildew growth, aggravating allergies and respiratory issues.

Data Source: Skarha, J. et al (2023), Heat-related mortality in U.S. state and private prisons:

A case-crossover analysis. PLOS ONE 18(3):e0281390. (Map: Leah Wang, 2023)

This map originally appeared in Heat, floods, pests, disease, and death:

What climate change means for people in prison.

- Health Implications and Prior Health Exposures:

- New Jersey recorded the nation's highest inmate mortality rate across all three COVID-19 phases, exacerbated by pre-existing respiratory conditions, overcrowding, and inadequate ventilation.

- During the 2023 summer wildfires, incarcerated individuals at the Garden State Youth Correctional Facility suffered severe respiratory issues due to hazardous particulate matter, with air quality index levels deemed very unhealthy.

Conclusion and Call to Action

Sydnie’s research highlights the urgent need for research-informed interventions and policy reforms to mitigate the compounded risks faced by New Jersey's incarcerated population. More comprehensive studies should assess first-hand experiences with the cumulative impacts of climate change on incarcerated individuals and relationships between climate risks, contaminated sites, and health.

Our Commitment to Environmental Justice

At Clean Water Action, we are committed to addressing these pressing issues and advocating for the health and well-being of all communities, including those incarcerated. In 2022, advocates of the incarcerated and Clean Water Action got the NJ Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) to conduct an evaluation of the quality, availability, testing protocols and cost of both tap and bottled water in NJ’s correctional facilities. While some progress was made in 2022, concerns about drinking water safety remain.

We are excited to announce our partnership with Sydnie Bogan and the Women Who Never Give Up organization as they seek to implement water filtration solutions in New Jersey's correctional facilities. X Braithwaite, our New Jersey Environmental Justice Organizer, is collaborating with Sydnie to help ensure the success of this initiative.

To support this vital cause, we have launched a petition to demand immediate action from state authorities to improve water quality and living conditions in New Jersey's prisons. Your signature can make a difference! Sign the petition here.

Together, we strive for a future where environmental justice is upheld for all, and we invite you to join us in this crucial endeavor.

_________________________________

References

Rosenblum, J. S., Liethen, A., & Miller-Robbie, L. (2024, April 23). Prioritization and risk ranking of regulated and unregulated chemicals in US drinking water. Environmental science & technology. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC11044589/

Zbarby. (n.d.). Health officials investigate seven additional cases of legionnaires’ disease reported in Mercer County, urge precautions to reduce risk of legionella growth. www.nj.gov/health/news/2023/approved/20230327b.shtml

Hazardous substance fact sheet - nj.gov. (n.d.). www.nj.gov/health/eoh/rtkweb/documents/fs/1902.pdf

Ethylene dibromide (dibromoethane). (n.d.-a). www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2016-09/documents/ethylene-dibromide.pdf

Pellow, David. (2017, October 27). Environmental inequalities and the U.S. prison system: An urgent research agenda. International Journal of Earth & Environmental Sciences. www.doi.org/10.15344/2456-351X/2017/140

Volatile organic compounds in your home. Volatile Organic Compounds in Your Home - MN Dept. of Health. (n.d.). www.health.state.mn.us/communities/environment/air/toxins/voc.htm

Suarez v. A1, Civil Action No. 06-2782 (JBS) | casetext search + citator. (n.d.-c). www.casetext.com/case/suarez-v-a1

Albert C. Wagner Water Quality Documents

Mercer County Correctional Center Documents

Skarha, J., et al. "An Overlooked Crisis: Extreme Temperature Exposures in Incarceration Settings." American Journal of Public Health, vol. 110, no. 1, Jan. 2020

Wang, Leah. "Heat, Floods, Pests, Disease, and Death: What Climate Change Means for People in Prison." Prison Policy Initiative, 19 July 2023

Pellow, D.N., et al.,, UC Santa Barbara, & Global Environmental Justice Project. "Environmental Justice Struggles in Prisons and Jails around the World." The 2020 Annual Report of the Prison Environmental Justice Project

“Climate Change in New Jersey: A Brief Introduction." New Jersey Climate Change Resource Center, n.d.

Cowan, K.N., Peterson, M., LeMasters, K., Brinkley-Rubinstein, L. "Overlapping Crises: Climate Disaster Susceptibility and Incarceration." International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 19, no. 12, 17 June 2022

Wu, Paloma, and D. Korbin Felder."Hell and High Water: How Climate Change Can Harm Prison Residents and Why COVID-19 Conditions ..." Fordham Urban Law Journal, vol. 49, 2022, pp. 259-300