On November 12, the Baltimore City Council held an informational hearing about mold in housing in Baltimore City. Council members heard from city agencies, housing activists, and community residents about the negative health impacts that mold can cause, particularly to people already dealing with health problems, and programs to address mold problems in public housing, rental units, and private homes. As the City Council wrote in its call for the hearing,

Mold is a health danger to many vulnerable populations. It grows where there is moisture; walls, ceilings, carpets, tile, or furniture can all be good environments for mold. Mold allergies manifest themselves through watery eyes, nasal stuffiness, throat irritation, coughing, headaches, and difficulty breathing. People that are immune compromised or have chronic lung illness can get serious lung infections from mold exposure. The Institute of Medicine has found sufficient evidence to link indoor exposure to mold to upper respiratory tract symptoms, coughs, and wheezing in otherwise healthy people, and to asthma symptoms in people with asthma. Many children in Baltimore suffer from asthma, and their health is particularly at risk if they are exposed to mold in their homes. The Baltimore City Council is interested in learning about mold in housing and how we can protect our citizens from its dangers.

Written reports from city agencies about mold in housing can be downloaded here.

Because of the link between mold and asthma, we wrote to the City Council to bring attention to a recent report by our allies at the Environmental Integrity Project: "Asthma and Air Pollution in Baltimore City." (PDF)

Dear Baltimore City Council Housing and Urban Affairs Committee,

Clean Water Action is a national environmental advocacy organization with over 11,000 members in Baltimore City. We work for swimmable, fishable waters in Maryland, for safe drinking water, and for environmentally safe and healthy communities. Conditions within people’s homes have an enormous impact on public health and on many individual health conditions, and so we thank you for holding the Informational Hearing about Mold in Housing called for in Council Bill 19-0148R.

I am writing to call your attention to a recent study by our allies at the Environmental Integrity Project that may be useful in analyzing the current and future public health impacts of mold, and how they fall on different geographic areas and demographic populations in the city in unequal ways. In December 2017, EIP issued a report, attached, on asthma and air pollution in Baltimore City that analyzed a recently released set of zip-code level data on asthma hospitalizations and asthma emergency room visits. While the focus of the report was on air pollution as an asthma trigger, the authors acknowledged in several places that many factors can act as asthma triggers, including mold. (See page 3 of the attached report.)

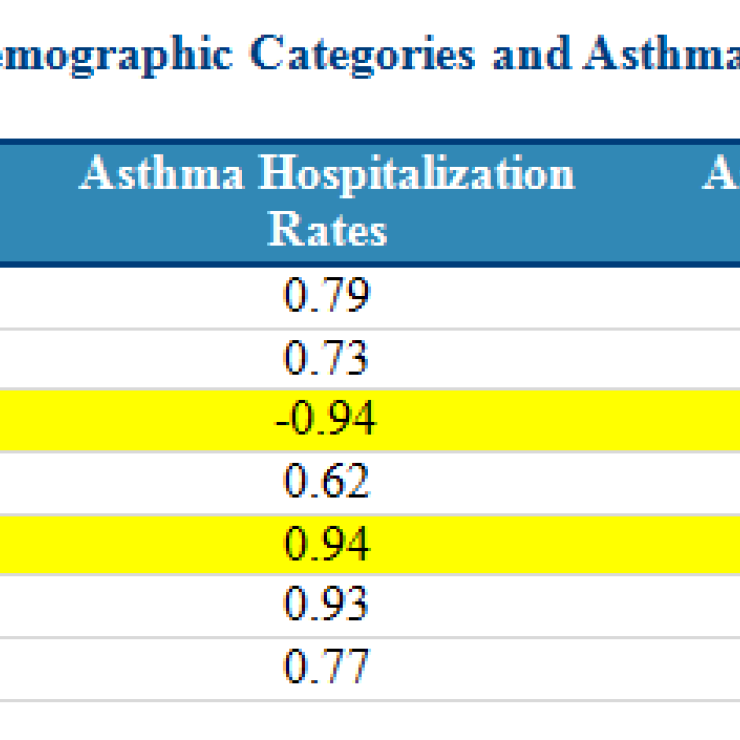

EIP analyzed the correlation between extreme asthma events in Baltimore and seven demographic markers of poverty. Table 5, copied below, shows the correlation between each demographic category and asthma rates. Correlation coefficients are interpreted as showing stronger correlation the closer that they are to -1 or 1, and weaker correlation the closer that they are to 0.

The table shows that rates of asthma events are very strongly correlated with measures of poverty in Baltimore, particularly median household income and % of population using Medicaid. Although EIP is not a group that specializes in housing or poverty issues, it is worth noting that the report’s authors concluded that: “[m]easures of poverty are strongly correlated with rates of acute asthma events in Baltimore, meaning that it is likely a combination of factors – including poor housing conditions and lack of access to preventative care – that is driving the high hospitalization and emergency room visit rates in Baltimore.” (See pages 45-46 of the attached report.)

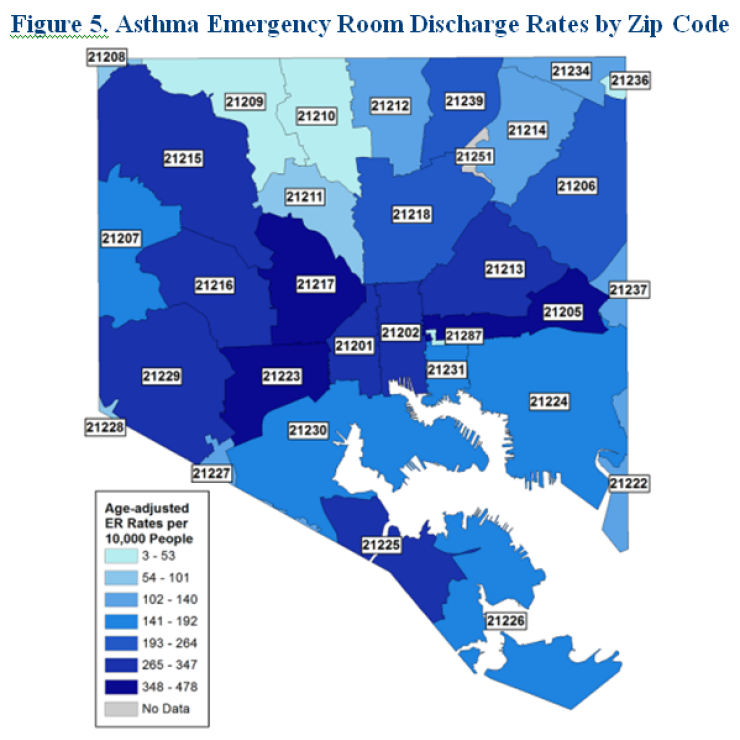

Factors like mold in housing that are known to contribute to asthma and other respiratory conditions deserve increased attention as the city considers public health interventions, particularly given the disparate impact that asthma has on people in poverty. Geographically, these impacts fall along familiar lines in Baltimore City, with significantly higher incidents of asthma found in historically-redlined areas of East and West Baltimore, as evidenced by the above figure. (See page 15 of the attached report.) Further actions should be taken by the Council to investigate how city policy might be changed to improve asthma outcomes in these areas, particularly regarding improving housing conditions.

I also want to bring attention to one of the recommendations for further investigation that the City Council may be able to help move forward:

4. The Maryland Department of Health Should Make Asthma Data Available by Community Statistical Area for Baltimore City.

EIP is extremely appreciative of the time and resources that the Maryland Department of Health has expended in making available the zip code level asthma data discussed in this report. We are also very grateful to officials within the [Maryland] Department of Health for taking the time to provide helpful input in responses to questions that we have raised about the data as we wrote this report. However, there is a way in which the asthma data could be made even more helpful to residents of Baltimore City. The Baltimore Neighborhood Indicators Alliance (“BNIA)” tracks poverty and a number of other factors in the city at the level of community statistical areas, which are clusters of census tracts, and issues annual reports on this data called Vital Signs reports. If possible without violating privacy requirements, the Maryland Department of Health should make asthma data available at this level for Baltimore City. This data would allow a direct comparison with many of the factors tracked by BNIA, such as measures of poverty and also other measures relating to health and quality of life, including housing. Being able to make a direct statistical correlation would assist in identifying the factors that are most contributing to the high asthma rates in Baltimore and could potentially identify any that might affect certain neighborhoods. (See pages 48-49 of the attached report.)

Encouraging the Maryland Department of Health to make this data set available to public interest organizations would be an extremely valuable way for the Baltimore City Council to improve public knowledge about the factors that may be exacerbating asthma trends, and how these trends may be correlated with housing stock and the prevalence of toxic mold.

As climate change threatens to bring more and more intense rainstorms to the mid-Atlantic region, and as our housing stock, stormwater infrastructure, and sewage infrastructure continues to age, it is important to consider what measures Baltimore City can take to reduce the factors that lead to mold growth in housing, and therefore reduce asthma triggers experienced daily by Baltimore residents. Please continue to push for improved housing stock, renovation, deconstruction, and high-quality affordable housing to improve public health.

Thank you,

Jennifer Kunze

Maryland Program Manager

Clean Water Action