In summer 2014 the residents in and around Toledo, Ohio were told not to drink, cook, or bathe with the water from their faucets. A massive growth of toxic blue-green algae got into Toledo's drinking water intake and the system had to be flushed. This toxic algae is mainly caused by nutrient pollution from farming activities with a little help from runoff from municipal wastewater systems and a boost from climate change. The rapid and large growth of blue-green algae (cyanobacteria) is known as a "Harmful Algal Bloom"(HAB). The drinking water disruption in Toledo drew increased attention to HABs, the toxic chemicals they can produce, and to impacts on people’s health, on wildlife, and overall water quality.

What are Harmful Algal Outbreaks?

Cyanobacteria commonly live in freshwater and are an important part of aquatic life. However excessive growth of these bacteria can release cyanotoxins, resulting in Harmful Algal Blooms, which cause damage to fresh water ecosystems, harm wildlife, livestock and pets, and threaten public health and drinking water supplies.

Causes of Harmful Algal Outbreaks

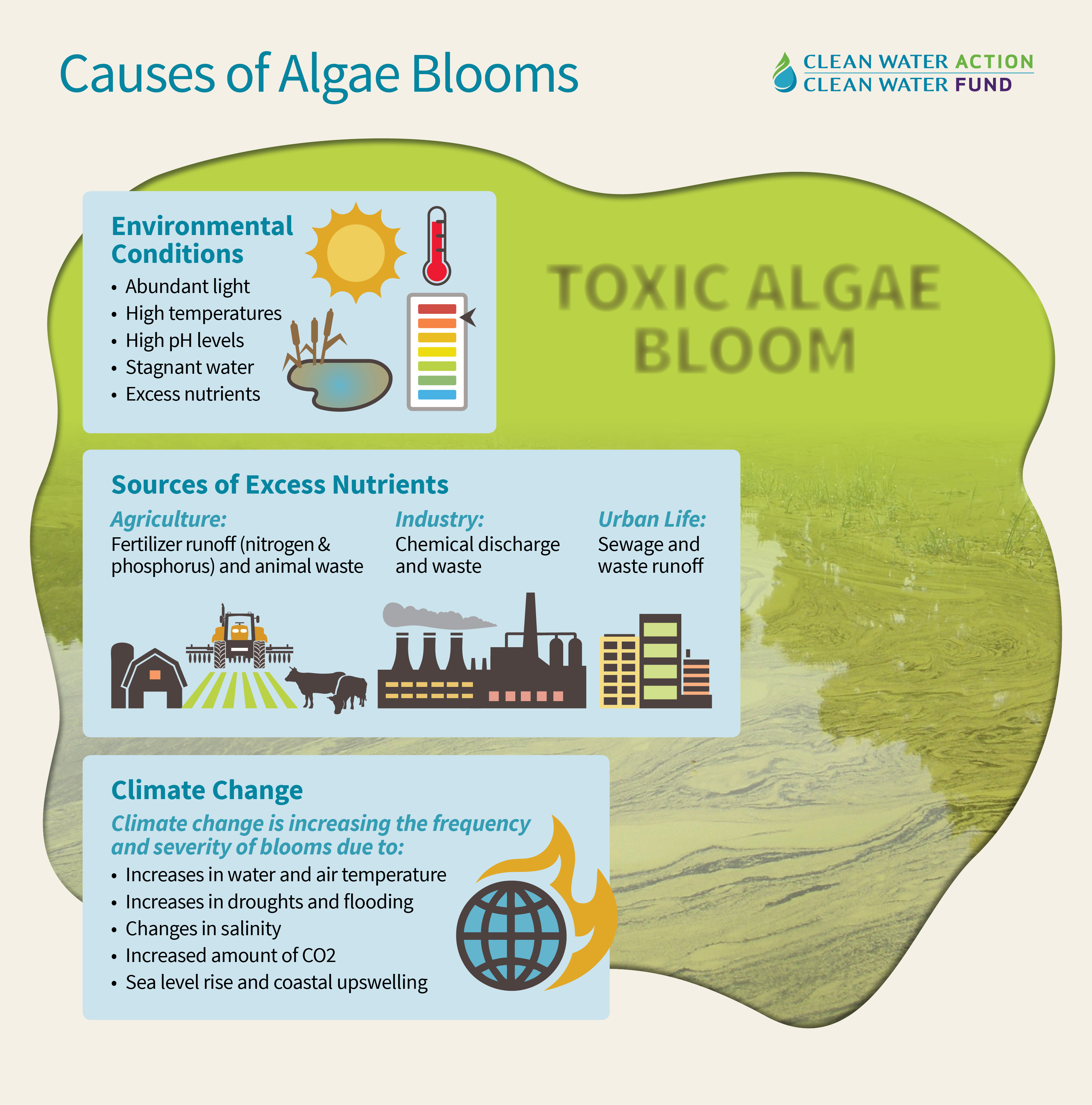

Freshwater Harmful Algal Blooms happen most often where there are high levels of nutrients like nitrogen or phosphorus present in warm, still waters like lakes, ponds, or reservoirs. They can also occur in rivers, especially during summer months. Aquatic ecosystems need nutrients to thrive but fertilizer runoff from agriculture, sewage and industrial discharges, and urban stormwater have added an excessive of nutrients into many of our nation’s bays, lakes and rivers.

Most scientists believe climate change is increasing the frequency and occurrence of HABs due to warming water temperatures, more sustained drought, and increased flooding, which means more polluted runoff in urban areas. For instance, in recent years algal blooms in Lake Erie have lasted into December and January. In 2015 some rivers, like the Russian River in Northern California, experienced higher frequencies of HABs exacerbated by California’s historic drought.

Overview of Health Impacts of Harmful Algal Outbreaks

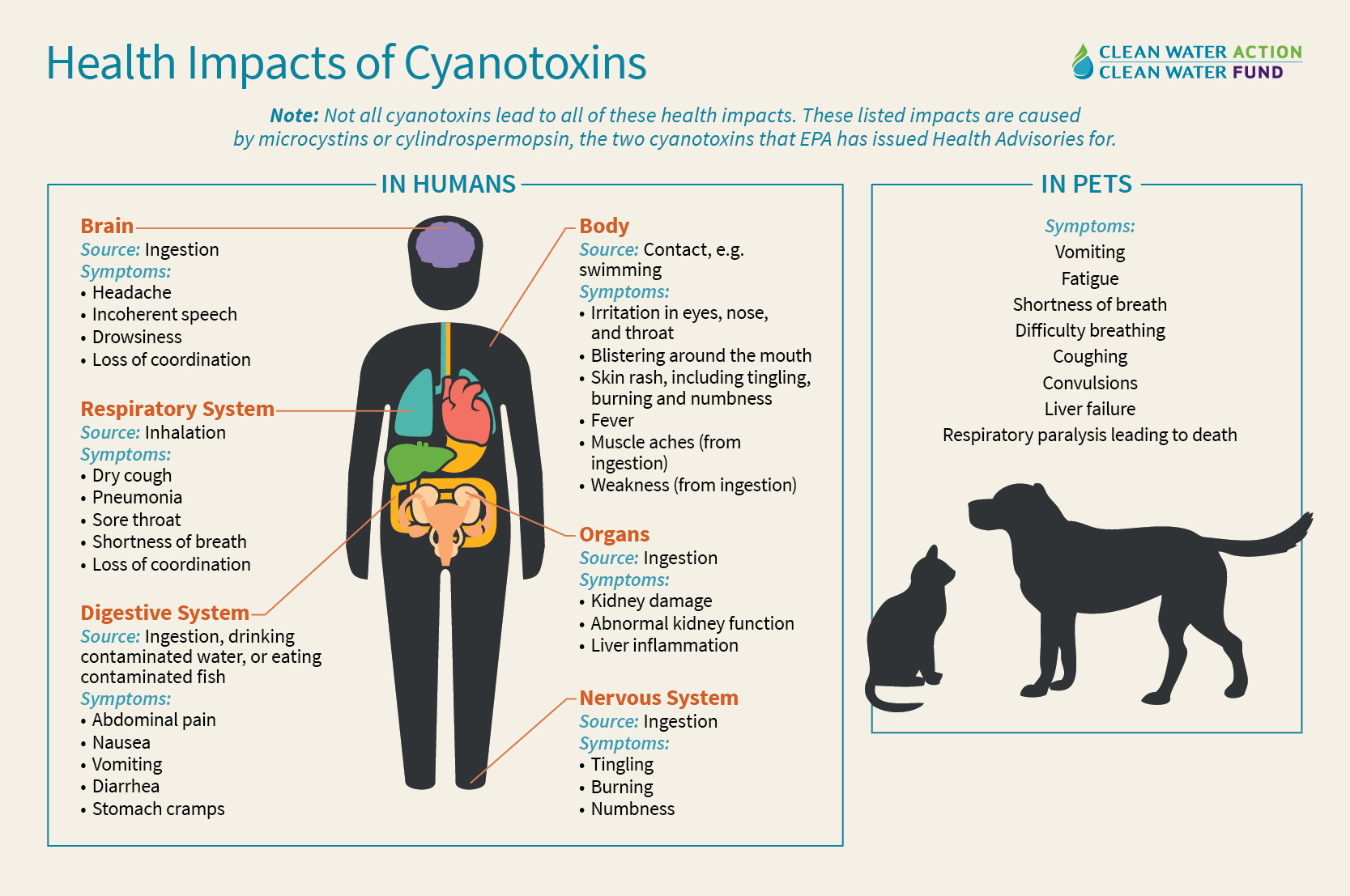

People and animals can be exposed to toxic algae through swimming, breathing in tiny airborne droplets containing algae when swimming or playing in water, swallowing contaminated water, or eating fish or shellfish contaminated with toxic algae. The impacts to humans vary from skin, eye, and throat irritation to vomiting, organ, and neurological damage and respiratory problems. Animals can be poisoned by drinking water or eating fish contaminated with toxic cyanobacteria. Pets are particularly vulnerable and dogs have reportedly died after drinking contaminated water or licking toxic algae scum off of their fur.

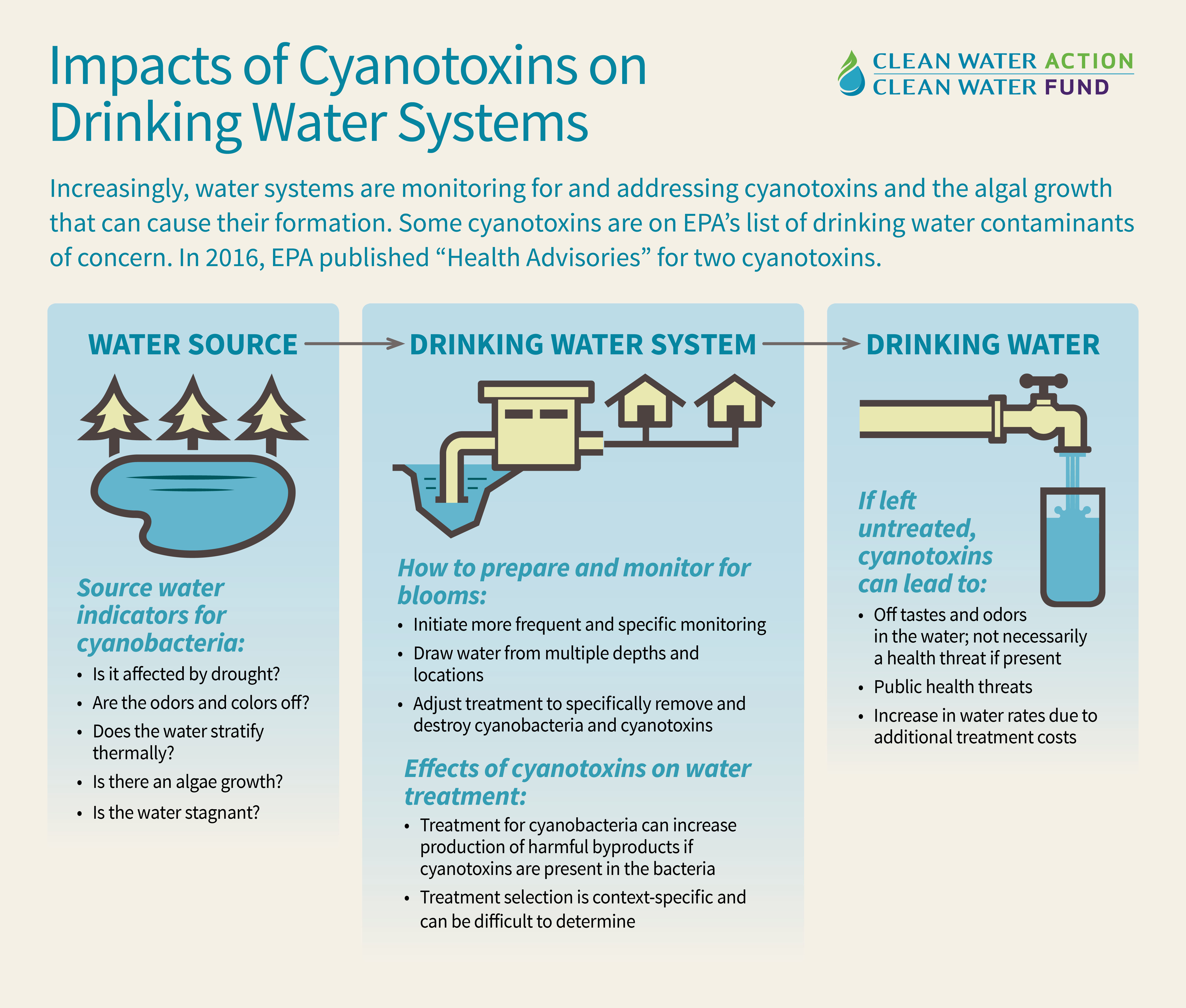

How Harmful Algal Outbreaks Impact Drinking Water

Cyanobacteria are a growing concern to water utilities that rely on surface water. Cyanobacteria that produce cyanotoxins are just one problem water utilities face. While not all cyanobacteria produce cyanotoxins, some produce unpleasant taste and odors. They can also interfere with the drinking water treatment process itself, including increasing the occurrence of potentially harmful disinfectant byproducts. Treating drinking water to remove cyanotoxins is expensive and that cost is typically passed on to water customers.

Protecting Drinking Water from Harmful Algal Outbreaks

The American Water Works Association (AWWA) has created a self-assessment “check-list” to help water systems that draw from surface water sources prepare for potential cyanotoxic events. To be prepared, water system managers need to understand the conditions that can trigger Harmful Algal Blooms. These conditions include high nutrient levels, warm water temperature, low flow and pH. Algal blooms can be transported close to drinking water intakes by wind or water currents. Systems also need to be able to effectively monitor for cyanobacteria, and, if necessary, treat for cyanotoxins when they are present in source water or draw raw water from a different intake location.

Regulation of Harmful Algal Outbreaks in Water

Currently there are no federal regulations to address cyanobacteria in surface water under the Clean Water Act (CWA). EPA has announced that it will soon propose new regulations to better protect people from exposure to harmful algal blooms when swimming or boating. There are also no Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) enforceable standards or guidance for cyanotoxins, though they are currently on EPA’s priority list of drinking water contaminants of potential concern.

In 2015 EPA issued 10-day drinking water health advisories (HAs) for two cyanobacterial toxins, microcystins and cylindrospermopsin. Though not enforceable, HAs are important technical guidelines to assist government officials and water system managers to protect public health from contaminants. More needs to be done to manage the conditions that enable HABs to occur in the first place, in particular reducing runoff of nitrogen and phosphorous pollution from agriculture. Drinking water systems and their customers are bearing the burden of monitoring for and preventing problems caused by upstream sources of pollution.

Learn more

- U.S. Environmental Protection website on Cyanobacterial Harmful Algal Blooms: https://www.epa.gov/nutrient-policy-data/cyanohabs

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) general information on HABs: http://www.cdc.gov/habs/

- “A Water Utility Manager’s Guide to Cyanotoxins” American Water Works Association & Water Research Foundation: http://www.waterrf.org/PublicReportLibrary/4548a.pdf