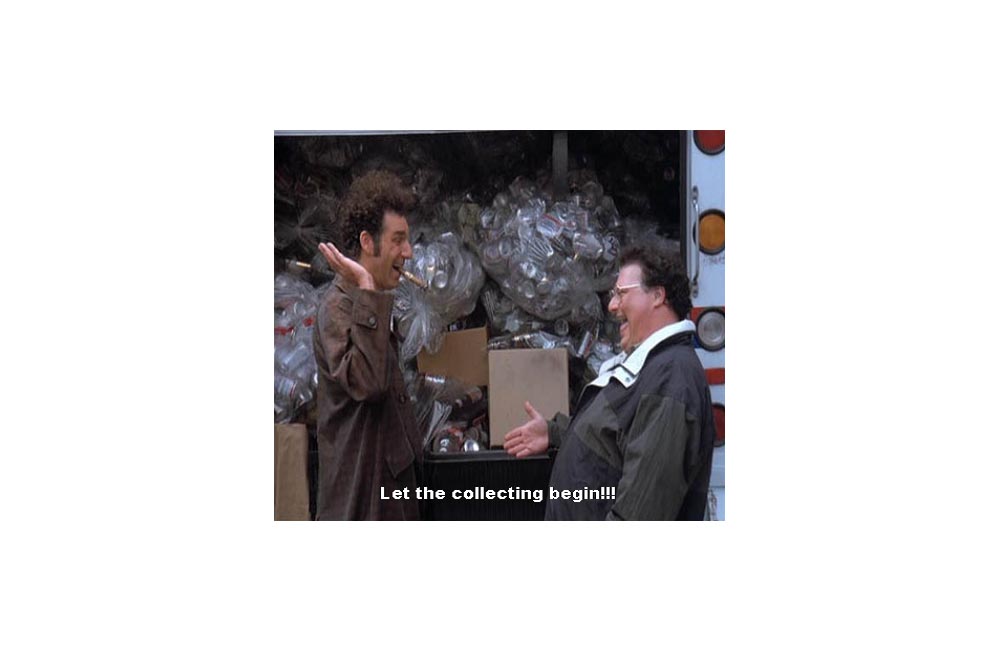

In a very memorable episode of Seinfeld, Kramer and Newman take off in Newman’s mail truck loaded down with empty pop cans to return in Michigan for a tidy profit of 10 cents per can. The scheme was hatched in Jerry’s apartment, and their initial run was to be a sort of test to see whether or not a massive operation of muling pop cans into Michigan to defraud our bottle bill program was feasible.

Thirty years later, a group of lawmakers want to stop this kind of fraud – unfortunately, they have also developed their own Kramer and Newman like scheme to raid the Bottle Bill. The bottle bill works like this – you pay a 10 cent deposit on each can or bottle of a carbonated beverage you buy, then return the can or bottle and get your dime back. Simple enough. But not everyone returns the bottle. So what happens to the money that goes unclaimed from cans and bottles that aren’t returned? That money is called the bottle bill “escheats” and is split -- 25% reimburses grocers and others who participate in the bottle bill program, and 75% goes toward state programs. 80% of the money that goes to the state supports Michigan’s contaminated site cleanup program. We need those funds – Michigan has more than 24,000 contaminated sites. Bottle Bill funding is critical to addressing these sites so we can avoid situations like the green ooze leaking out of 696 and potential nuclear waste falling into the Detroit River that we’ve seen in the last two months alone.